|

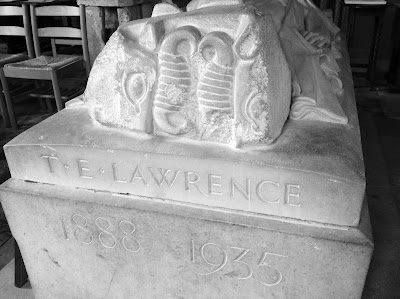

Lawrence effigy in repose

|

"The shock of T.E.'s death. Yes, when we were getting over it I had a letter from Buxton asking me to attend a committee which would plan a National Memorial."

The artist and sculptor Eric Kennington was among a select group of people brought together to discuss a fitting memorial following the death of T.E. Lawrence in 1935. "As far as I can remember," Kennington recalled many years later, "the other members were Buxton 'in the chair', Lady Astor, who soon elbowed him out of it and was in it herself, Newcombe, Storrs, Bernard Shaw, Lionel Curtis, Sir Herbert Baker."

Robin Buxton was Lawrence's banker and former colleague in the desert war. Lionel Curtis was an old friend and advocate of Imperial Federalism, which after its rejection in 1937 gave way to the idea of a Commonwealth of Nations. Sir Herbert Baker was an influential architect who with Edwin Lutyens had created New Delhi which became the capital of the British Raj in India. Baker had given Lawrence sanctuary in an upstairs attic room above his studios in Barton Street, Westminster, allowing Lawrence to work undisturbed on his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

The committee was slow to come up with suitable ideas. "Then Baker said he had asked T.E. once what his idea was for a monument to himself," Kennington recalled, "and his reply - "The largest mountain in Arabia carved into a likeness of himself!" This amused Sir Ronald Storrs who interjected, "What a fine target for the Arabs - they'd get his nose first shot." Storrs, formerly assistant to the High Commissioner in Egypt followed by spells as Governor of Jerusalem and Cyprus, was an old friend of Lawrence and was instrumental in inviting him to assess the situation in the Hejaz at the start of the Arab Revolt. He knew that no grand ideas were ever formed by committees, but a lot of foolish ideas died there. Then Baker said, "What about an effigy? We have a distinguished sculptor here." Kennington had been lying low throughout the proceedings but quickly produced some sketches which were generally accepted. Then the matter went very quiet for several months. Kennington turned to the one man he could trust to give him a straight answer. He wrote to Stewart Newcombe who replied, "Nothing doing - it's all off. They aren't going on with a National Memorial." This was a blow especially as leaflets had gone out requesting donations and had been signed by the committee members which now included Churchill, Allenby and Augustus John. The idea was quietly dropped.

|

| Hand on Arabian khanjar dagger |

Two years passed when a chance encounter at Oxford railway station between Kennington and Curtis reinvigorated the idea of an effigy. Curtis remembered their previous association and said it was a pity that the scheme for an effigy had fallen through, adding, "I wonder what it would have looked like?" "You'd better come and see it," Kennington replied. "It's almost finished."

|

| Legs crossed at the ankles |

Lawrence's brother, Arnold, came to see it and immediately offered to buy it from Kennington. "What's this worth to you?" he asked bluntly. Kennington gave a price of two thousand pounds and a cheque was drawn up there and then. But where to place it? It is not clear who first suggested the tiny parish church of St. Martin's-on-the-walls, Wareham in Dorset, but when seen today Kennington's effigy rests in the most wonderful example of a 1000 years old Anglo-Saxon church, accessible to all and in perfect harmony with its surroundings.

|

| St. Martin's-on-the-walls, Wareham |

Kennington sculpted the effigy in the style of a recumbent figure with one hand resting on the hilt of a curved Arabian khanjar dagger and one resting loosely at his side and with legs crossed at the ankles in the style of a thirteenth-century knight. Cross-legs and sword handling were features of effigies during this period, created to depict an image of repose and peace which complemented further characteristics which represented military vigour and alertness. This style persisted until the middle of the fourteenth-century when it fell out of favour to be replaced by the praying, straight-legged effigy. The meaning of the cross-legged feature was generally thought to have originated from Knights Templars or Crusaders who had died in the Holy Land, had died during the journey home, or had simply travelled east as a pilgrim or soldier. The romance of the pilgrim soldier persisted and was especially strong in the sixteenth-century, long after the period of the Crusades, reinforcing the theory. However, this crossed-legged Crusader connection has since been refuted by historians. Kennington, in reproducing the image of a 13th-century knight, was tapping into the popular beliefs held at the time.

Kennington was aided in his work by photos of the progress of the sculpture made by Wing Commander Reginald Simms, an amateur photographer and a former colleague of Lawrence at Bridlington during his RAF service. These undoubtedly helped Kennington during the development of the effigy, highlighting any errors. This ultimately resulted in a fine piece of work with an exquisite likeness of Lawrence in repose but also with an alertness and readiness for further action as depicted by his resting hand ready to un-sheath the curved blade. This feature was particularly pertinent when the effigy was finally placed in St. Martin's in September 1939.

Two years earlier, Churchill had contributed a piece to T.E. Lawrence By His Friends, a collection of reminiscences or impressions of Lawrence by those who knew him or had worked with him - a 'gallery of partial portraits', as Arnold Lawrence, the editor, put it. Churchill submitted a revision of an earlier obituary article published on 26 May 1935 in the News of the World newspaper, only seven days after Lawrence's death. He wrote, 'I fear whatever our need we shall never see his like again'. Churchill used much of this article at the unveiling of a memorial plaque by Kennington at the Oxford High School for Boys on 3 October 1936, an event at which Colonel and Mrs Newcombe attended and where Elsie Newcombe confessed to a bemused E.M. Forster that "Mrs Lawrence [T.E.'s mother] lovs me so much that I may kiss her here here with my rouged lips and leave spots on her face and still she doesn't mind."

Churchill included the Oxford text with further amendments in his 1937 opus Great Contemporaries where he made significant changes in both words and tone at a time when he was languishing in a political wilderness. With ominous world events pointing to another world war - in March 1936 Germany had reoccupied the Rhineland and four months later saw the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War - he used the occasion to highlight a pressing need for political effect. "All feel the poorer that he has gone from us. In these days dangers and difficulties gather upon Britain and her Empire, and we are also conscious of a lack of outstanding figures with which to overcome them." This was not just about Lawrence. If Churchill had been side-lined at least he was able to remind his audience he was still available.

Even Lawrence's role in the RAF was utilised for Churchill's own political aims. In Friends, Churchill wrote simply that Lawrence experienced twelve years of "honourable service" in the RAF as an air-mechanic, concerned with the "mechanism of aeroplane engines, the design of flying boats." Two years later this employment was set aside in favour of a more far-reaching role that was used to bolster Churchill's own arguments for the strengthening of the aerial defence of Britain in line with the growth of the Luftwaffe. "Those who knew him best miss him most; but our country misses him most of all. For this is a time when the great problems upon which his thought and work had so long centred, problems of aerial defence, problems of our relations with the Arab peoples, fill an even larger space in our affairs."

With the spectre of war with Germany looming on the horizon, the tone of Churchill's revised portrait of Lawrence in Great Contemporaries became elegiac and inspirational to stir the emotions of the British public about to face their finest hour and in need of an Arthurian figure who was merely waiting for the call to arms once again. Kennington's effigy fitted the bill exactly. It would also not be long before Churchill was recalled from exile.

NOTE

Photographs of Eric Kennington's effigy of T.E. Lawrence by Kerry Webber (December 2015), courtesy of the Rector and Churchwardens of St. Martin's-on-the-walls, Wareham.